The Tao symbols of balance so prominent on the Korean flag welcomed me when I arrived to settle into my host country – South Korea. Our group of newbie faculty went in action mode at our UMUC Korean headquarters located at The Eight Army compound at Jongsan. It was the social hub and distribution center for our course materials and supplies. Most importantly, it served as the starting point for our teaching assignments that radiated to military posts/ camps/ bases throughout the Korean Peninsula. We soon got the big picture of our institution that included UMUC field representatives at our assigned teaching centers who managed the daily operations to help make our teaching successful.

Although primitive by today’s standards we valued the tools available to us. They included mostly typewriters and copying machines. Personal computers were still rare. My newly purchased laptop did not have an internal hard drive, the RAM was practically non-existent making this “prized” tool rather labor intensive. Landline telephones kept us connected. It was the age before the world-wide-web and smart phones. Regular email was still a scientific fantasy.

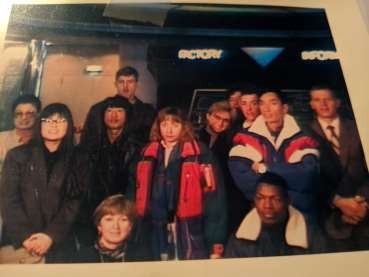

In true UMUC overseas style we met our local team of faculty, staff, and administrators in a social setting as we got our course assignments, teaching material and teaching destinations. Many assignment destinations were to the north in army camps close to the DMZ, some at Jongsan in Seoul others to the south included Camp Humphreys, Osan AB and Kunsan. We waited with trepidation to find out where each of us would be going. Some uneasy stories circulated about living on the economy – private homes – in the winter when cold temperatures required complicated heating systems to stay warm.

I was among the lucky ones. My first assignment was at Camp Humphreys about 40 miles away

– a rural place to the south. Surrounded by rice paddies and small villages Camp Humphreys was a high security, multi-forces, military site. It was an original. The camp was established during the Korean conflict, complete with the first MASH unit.

Getting started, I boarded one of the many comfortable fully air conditioned busses (a true blessing) corralled among many others at Jongsan. My two suitcases now bulged with new purchases from Itaewon, a breathtaking shopping haven in Seoul. A new box of belongings contained materials for the three courses I was to teach in my first term. I now had a manual about military rules that included a page of military acronyms to help me “learn the military jargon” (APO, MP, MWR, NCO, PT, TDY, etc.) that soon become routine in my vocabulary. I read this with care while glancing at my new host country outside the bus.

Korea was in a rapid growth stage in 1990. Having hosted the Olympics two years earlier, it now boasted new transportation networks including a subway system and an expansive highway going south. The highway I was travelling was designed to become an alternative runway. Planes could land or take off from there in case of emergencies if the North Koreans attacked. It was one of many examples of the flexible planning of the Korean-American relationship.

Road construction throughout Korea intensified during my year in Korea. The government had just approved consumer credit that had Koreans euphorically rushing to buy their own Korean made cars. It was a great strategy to create demand for their car manufacturer. Traffic was to increase tremendously.

Living on a military post was a new experience for me. I was fortunate that UMUC had arranged for me to temporarily live in military housing at Camp Humphreys. When I arrived and completed my registration, and got a modified Quonset hut with many small rooms. The “coed” washroom was a challenge – I had to wait to enter after knocking on the door, if no one was inside I would enter and lock the door from the inside to do my business that could include a shower and a wash. My room was furnished in simple rustic – bed, night table, table, tiny refrigerator, window and closet. I was home and now alone.

Aloneness was the norm for many. The camp was listed as un-accompanied, meaning that families of the troops remained at home in the U.S. Aloneness temporarily disappeared for some as residents in my Quonset hut called home during the night – from the echoing hallway outside of my room. It could go on for hours as caring voices spoke to friends and loved ones at home keeping up with essentials and sometimes trivia. It kept me awake for the first sleepless nights.

But, I soon got used to it as it became a normal nightly routine.

The sound of boots on the ground and “Jodi chanting” woke me as groups would do their Physical training (PT) on their pre-dawn run. It became part of my morning background noise. Within the first week. I slept through that as well as I adjusted to military life. I learned to prepare for the day when the reveille announced the beginning of the workday.

The small village outside of Camp Humphreys benefited with obtaining clean drinking water with the taps on the outside walls for locals to get large quantities of free water.

My life on base was secure. I was surrounded by people in uniform both U.S. and the KATUSAS who were a Korean- American force separate from the Republic of Korea (ROK) force. I would interact with many civilians both American and Korean who worked in the shops including the Burger King, or those who performed other support functions.

My self-guided orientation included a brief time to explore the base, dodge caterpillars and buy basic foods to keep in my room. My newly minted military ID gave me many valued privileges that including: permission to shop at the commissary, use of the amazing military gym, library, use of military mail – making sending packages to my loved ones at home inexpensive, use of military busses,and to eat at the officers club, and more.

There was little time to waste though because my courses needed to be designed and typed at the education center a short walk away. Pronto!

I conducted my classes at the Education Center on site. To this day, I love the military students. They were respectful, polite, and at times a bit humble to learn. They asked questions, interacted well with good eye contact and great posture. All were fit from their regular physical training. Even when tired in the evening they sat politely and erectly in their desks. They listened. My students were a picture of diversity in race, gender and age. There were multiple regional U.S. accents – many from the southern states. Students were required to wear civilian clothing -rather than come in uniform – as part of military policy to avoid intimidation because of rank. Some civilian contractors and KATUSA personnel also took my classes. It was an integrative environment of learning that was natural there. It was a wholesomeness of equity and respect during my UMUC career.

They came ready to learn – many had joined for the education benefits. They were my kind of people because education made a huge difference in my life. Education took me from a meager life with few options to many options.

My teaching philosophy had been influenced by my senior thesis for my undergraduate degree in history. It focused on Hu Shih – a Chinese intellectual and colleague of John Dewey. His philosophy stated that to teach was an ethical endeavor because it established a thinking base in those we teach that was everlasting. According to Hu Shih, teaching poorly or teaching well leaves a lasting impression in either case which he called, social immortality. By immortality he meant that there would be a continuing connection with the students and their thread of contacts with the ideas and behavior of those who taught them – parents, friends, teachers and other people of influence.

The other major influence for my teaching philosophy was my professor who had given me one of my references to support my application to UMUC – Peter Drucker. Drucker’s philosophy for both business and the self was, to always add value. To teach was to add value to a student’s knowledge and experience just as a business person needed to add value to the products or services they offered to their client. With these good thoughts, coupled with life experiences in business, as a parent, and a strong can-do attitude, I started my teaching career with UMUC. It was to last well over 20 years.

I transitioned to live at OSAN Airbase within a month of arriving in Korea to enjoy the comforts of a small modest apartment in a modified two story Quonset hut. Billeting apologetically considered it substandard housing. No problem. It was luxury to me. I had a bedroom, a small annex with a table for course prepping, and my own bathroom including a shower.

It was a social place with people who became my friends while preparing and sharing meals in the community kitchen and eating area. We all contributed to the services of a part-time housekeeper. She spoiled me by doing my laundry, cleaning my room and to my delight, polished my shoes. It was a luxury I never enjoyed before or have since.

My classes were scheduled for eight week periods with a short break between to grade and plan for the next session that soon followed. In my usual hands-on practical teaching style I added value to the student experience by initiating a series of field trips to Korean companies a short travel distance away. Our trip to Samsung Company was a big hit with everyone. We learned about their recruitment style that focused on hiring young women who had the fine-tuned finger dexterity needed to assemble tiny components into television sets and other electronics. The company’s paternalistic management policies included company housing for these women to keep them healthy and close to work. We learned much about Korean manufacturing.

At Samsung company, our tour ended with a futuristic demonstration that seemed much like science fiction to us. We had our doubts that Samsung could develop remote access to electronics in a house to include setting the thermostat, starting the coffee machine, or opening or locking doors remotely. We were polite when we thanked them not knowing that these technological innovations were to become a reality soon. Other company visits included a trading company and a pottery company producing amazing high quality artwork.

It was with great honor that I agreed to serve as the master of ceremonies (MC) at the Osan Community College of the Air Force graduation in the spring of 1991. The Education Service Officer (ESO) asked me to introduce the graduating class and discuss the value of education.

The audience was full of students and senior officers. Then, with the help of a senior officer, I gave each graduate his or her diploma. It was a new challenge of learning to do the “shake and take” ritual with each student. It took practice, focus, and some nervous energy. It proved to be a success and is a pleasure to remember to this day.

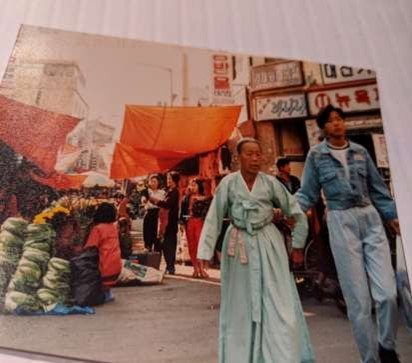

I explored my surroundings. My walks outside Osan AB gave me a good sense of life in the town of Songtan and the rice fields located around the base. Construction sites showed men wearing backpacks loaded with bricks climbing on ladders to bring the bricks to others up high who took the materials to build them into walls. In the evening, I could see groups of people through open windows in what appeared to be impromptu assembly rooms in private houses as they worked on sewing gloves or other items. The cottage industry was still very much a part of the economic system then.

I was fascinated by the care it required to plant and maintain rice paddies and then harvest the rice and dry it. I watched this through all the seasons and was impressed with the tidiness each step reflected.

Red peppers were a cash crop for some households and these were spread in neat circles to dry in court yards. Roof tops were lined with assorted earthenware pots containing kimchi, a sign that Koreans were strategic thinkers in maintaining their food supply.

Small children played in the street near their homes wearing only long T shirts and no bottoms – a practical way to avoid diapers while they were still not completely toilet trained. Older women often sat on their haunches nearby peeling green onions to bundle them into what appeared to be market size packages.

Sad and unsettling scenes were the dog cages on trucks and dogs in caged yards that were intended for a select restaurant market that specialized in dog meat on their menu.

On base and outside were many entrepreneurial Koreans – painters, tailors, shoe makers, printers of business cards, etc. With typical upbeat personalities, Koreans were ready to make a deal. It was possible to bring a picture of a favorite shoe or another item such as a dress or suit and ask to have it copied into new material. They would measure and determine your size and schedule the delivery date – sometimes only a day later. It was a fascinating business interaction.

Sometimes there were mistakes made and it was necessary to redo the order. No problem. With a happy smile I would be told –”we fix” and usually by the next day. It was a happy solution that resulted in many of us fondly calling Korea the “Land of Almost Right” during that time. The fix was always done “right”!

The underlying Confucianism in the Korean culture established a personality base with a respect for elders, a love for wisdom and a strong work ethic. They are my kind of people. I was glad to get to know them. I found them to be resilient, confident, with a sense of humor and possessing a great love for the outdoors. A Korean friend told me that Koreans were like their national flower the “cosmos” which is hardy and resilient. Cosmos bend with the wind but rarely break in a storm. Cosmos flowers were everywhere and grew tall and sturdy. I watched them from the back of the bus weaving in the flurry of wind the bus created when we passed. I now plant them in my garden, a beautiful reminder of Korean strength and determination.

Winters in Korea are very cold. Many wear masks to avoid breathing the icy air that could sear the lungs and result in a deep congestion and cough we called the Korean Crud. The congestion could last the whole cold season. But a Korean friend brought me a home remedy her mother kindly gifted to me of shaved ginger, honey and lemon juice in a jar. I was instructed to put portions of this in a cup of boiling water and sip it slowly so that the congestion would loosen and eventually disappear. It worked like magic letting me enjoy the winter healthy and without wearing a mask.

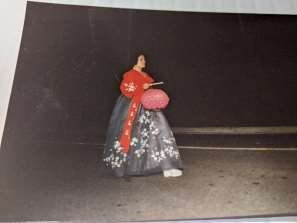

Although my teaching schedule was full and changed every two months, I participated in many Morale Welfare Recreation (MWR). field trips. These included a full day at the Korean Village where traditional dancing, cultural artifacts and beautiful landscaping gave the visitors wholesome understandings of this country that had a history of invasions yet survived and prospered each time while also creating beautiful art.

One MWR sponsored trip was an ominous experience. I had seen the sign “270 K to the MIG Alley” on base and now connected with the danger this sign warned about. To prepare for the trip, all participants were given strict instructions on what to wear – it needed to be professional. Sloppy clothing was not allowed. We also had behavioral guidelines that included not to point or laugh when touring the negotiation room at the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone).

Once at the DMZ, our bus drove slowly along the border and stopped where we could view a North Korean flag that weighed 100 pounds and was too heavy to fly. Pathetically, it hung limp.

Behind in a distance was a façade similar to a stage screen with panels of prosperous looking buildings painted on it. A loudspeaker welcomed us “Americans to the land of the prosperous Democratic Peoples Republic”. It was an embarrassingly amateurish scene of a fraudulent display of a country desperate to convince us of a prosperity they did not have. We said little. It left a lasting impression on me for what I did not want in my life. I got a deeper appreciation of our mission to keep South Korea a free nation.

Aloneness vanished with my activities. It was great fun to become a member of the Hash House Harriers. The Harriers is a running group that called itself the “drinking club with a running problem”. It rounded out my active social life in Korea. The Harriers have a long tradition in Asia going back many years as an activity the British introduced in colonial Burma. It spread throughout Asia and still exists around the world. It is made up of a somewhat nutty group of runners who set a new trail the day of the race that can lead to dead ends and may require many revisions and back tracks.

Our local Osan group attracted people from places as far away as Seoul each Sunday at two. There were at least 100 regulars who earned points with each run. We were rewarded with a provocative nickname and a series of bells for our shoes or clothes with every fifth run. The running races required stamina and the smarts to avoid dead ends that were set to trick us. I usually came in among the last but was always cheered and applauded with great gusto. We had the spirit shown among highly fit people who also enjoyed a cold beer after a run. It is a memory of great fun during my time there.

Paula Harbecke became our Asian Division director when Julian Jones left in the spring with his family to return to the U.S. Paula proved to be another excellent addition to our system. On her visit to Korea she gave each of us time for a mutual “getting to know each other” session. It was good to share my positive experience in the Asian division. Paula kindly asked me if I had a wish for my next assignment. At the risk of sounding ungrateful for my time in Korea, I said yes, I would very much like to transfer to the European division to familiarize myself with the country of my birth – Germany. Thankfully, Paula made this possible and I left Korea in the summer of 1991 to transfer to the European Division starting in August 1991.

When my plane back to the U.S. left Kimpo airport, Soviet Aeroflot Airline planes intermingled with Korean Airlines and Northwest Airlines planes on the runway. It was a sign that the world was changing rapidly. Our plane back to Seattle had 9 Korean babies on board who were going to their adoptive parents in the U.S. My personal belongings had expanded from two suitcases and a small crate to an additional 10 boxes full of gifts of running shoes, gym suits etc. for loved ones that were mailed home via the military post to my address on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State.

It was a sweet brief homecoming and immersion to exchange stories of the year with family and friends before leaving for Europe in August. The world was rapidly changing. The Soviet Union would collapse and Germany would reunify. Another great adventure was about to happen and I would be there as a witness – thanks to UMUC in Europe.